Daniel Contreras

Myriam Pajuelo, Aldo Panfichi Sanborn and Héctor Jara

The content of this news item has been machine translated and may contain some inaccuracies with respect to the original content published in Spanish.

National pride! Astronomer Dr. Myriam Pajuelo and her research assistant Aldo Panfichi Sanborn, professor in the Physics section and student of the Master in Physics at PUCP respectively, are the only Peruvians of the official team of researchers who collaborate voluntarily in the Double Asteroid Redirect Test (DART).

Led by NASA, DART is an ambitious and unprecedented mission: it is the first planetary defense test mission designed to change the course of an asteroid. Thus, at 6:14 p.m. this Monday, September 26, a space probe is planned to deliberately collide with the moon Dimorphos, a satellite of the near-Earth asteroid Didymos - which was chosen because it poses no real threat to the planet - with the goal of altering its course and deflecting it.

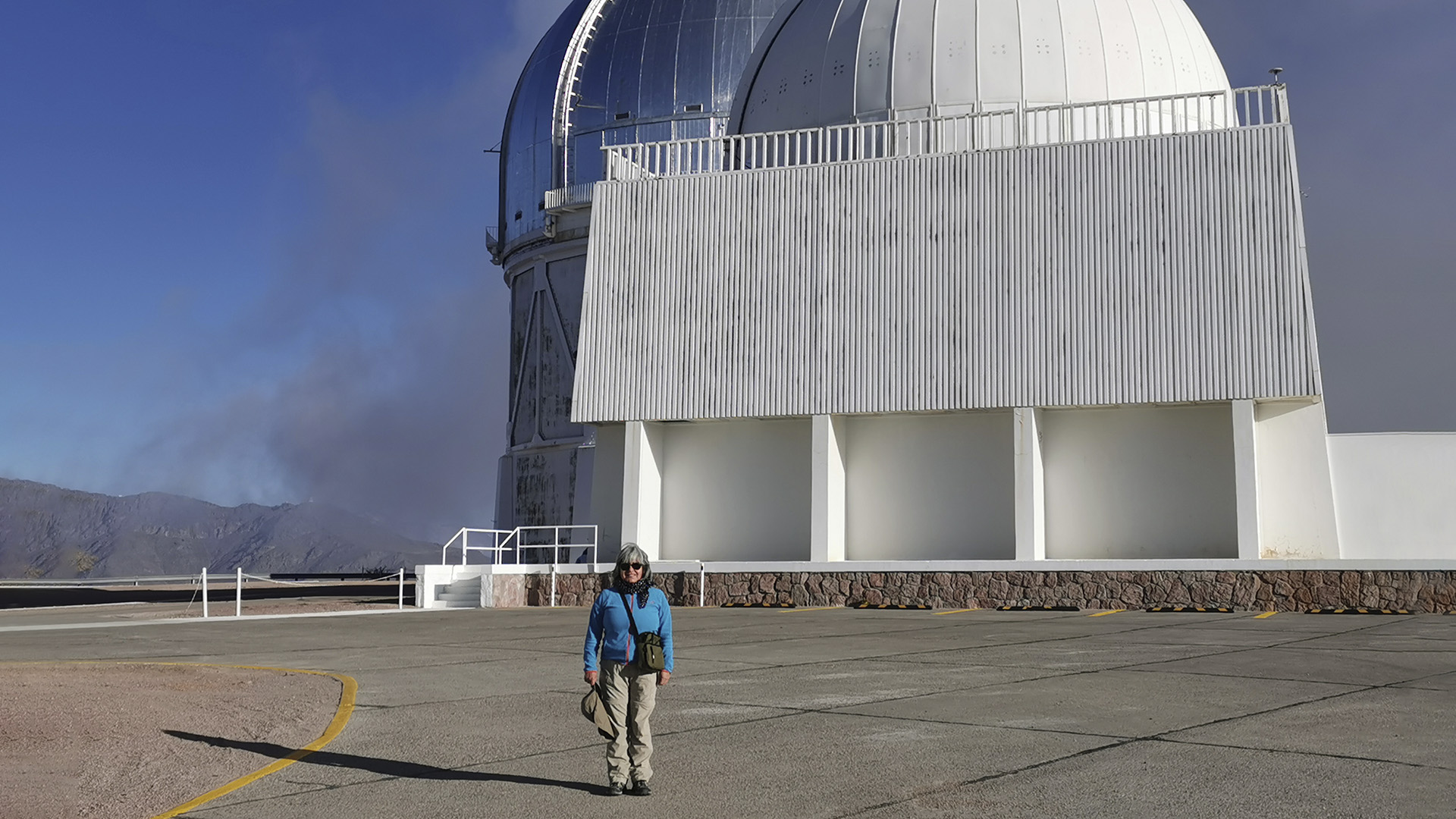

Two weeks ago, Pajuelo and Panfichi were at the Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory (Chile) as part of a project for the study of near-Earth asteroids (NEAs), funded by the Research Support Fund (FAI) of the Vice Rectorate for Research. There, at 2,200 m.a.s.l., the PUCP scientists were able to take a close look at Didymos from a privileged position. As a result of their observations, both researchers were incorporated into Team DART.

Professor Pajuelo is a recognized expert in the study of asteroids and other smaller bodies in space. In fact, last year, the International Astronomical Union named an asteroid after her in recognition of her work. And it is from this extensive experience that he recognizes that this will be a historic event. The mission will have great implications for strengthening our planetary defense against potential collision events with minor bodies such as asteroids and comets, whose probability, he points out, is never zero. From the probe's impact with Dimorphos, DART seeks to understand the feasibility of altering the orbit and course of an asteroid with this specific mode.

"Basically, it's about making two things collide in space and seeing what happens, like a child's game. In physics jargon we would say it is a transfer of momentum," explains the astronomer.

The big difference: Dimorphos is 160 meters in diameter. The DART spacecraft, which is about the size of a car and represents a cost of US$ 330 million, will impact at a speed of 6.5 kilometers per second. Although the impact will be comparable to the explosion of 3 tons of TNT, the deflection in the trajectory of the double asteroid should be small but constant. In this sense, Pajuelo points out that the monitoring of Dimorphos will continue for weeks and months to see the evolution of its orbit.

Using the SMARTS telescope at the Cerro Tololo observatory, Pajuelo and Panfichi were able to collect, during 4 consecutive nights, key information about Didymos in the form of photometric data. Thus, they have recorded the speed of its rotation or the physical conditions of its satellite Dimorphos. This telescope, 90 cm in diameter, has a large aperture, a highly stable base, and a cold chamber that provides a linear response and allows them to capture the light signal from the asteroids.

"This helps to define more precisely how Didymos and Dimorphos move. It is now critical to have as much knowledge as possible about this system," says the astronomer. The DART mission, which recognizes both PUCP scientists among its members, is led by the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory.

"A high concentration of observations of Didymos is required so that its motion can be monitored in detail before, during and after the impact", complements Panfichi Sanborn, who holds a Bachelor of Science degree from the University of Chicago and, in addition to studying for a Master's degree in Physics, is a pre-doctoral fellow in the Department of Science. He also explains that the current position of the asteroid in relation to the Earth's orbit allows its observation from the southern hemisphere, which gave the researchers a significant advantage over observers from the other hemisphere.

In contrast to the major powers, Peru's development in astronomy-related topics is still incipient. In this context, carrying out projects such as Pajuelo and Panfichi represent a window of opportunity for local scientists to accumulate experience in the field.

"This is the first time I have been able to make an observation of this type, from the site, and using a large and powerful telescope. It was an excellent experience and I feel I learned quite a bit," says Panfichi. He hopes that the field of astronomy and science in general will receive the necessary boost so that more young people can access opportunities like his.

"Dreaming of having telescopes and instruments of this size in Peru is perhaps a very big leap, but we could have agreements promoted by the State for their use," concludes Pajuelo.