Daggiana Gómez

The content of this news item has been machine translated and may contain some inaccuracies with respect to the original content published in Spanish.

This week, the PUCP and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) will hold the international workshop Latam Health 2022. This workshop will bring together researchers, professionals and managers leading medical technology innovation in Latin America in Room UNO of the PUCP campus. Thus, between 23 and 25 June, international specialists will work intensively and share their successful experiences.

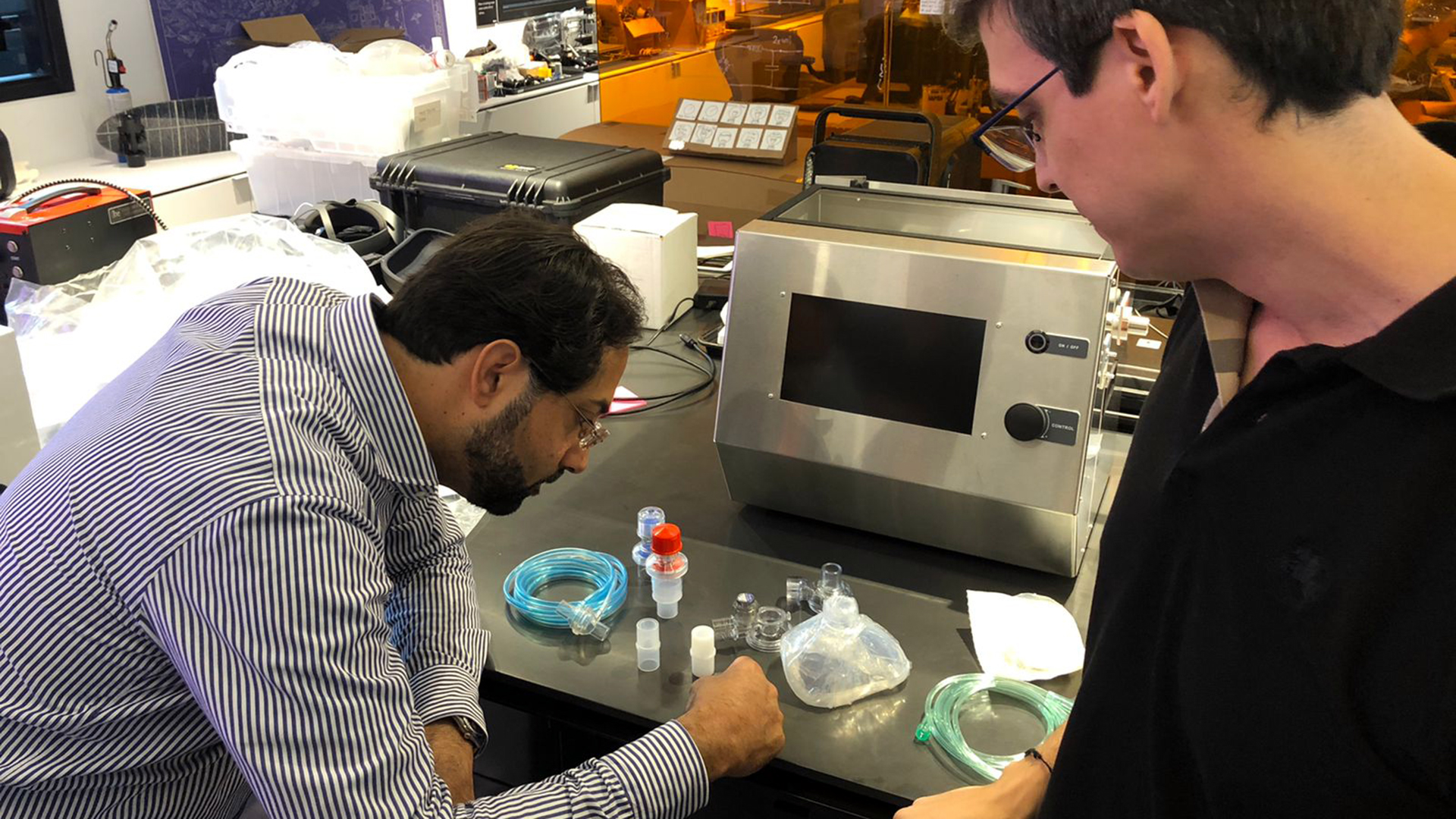

This event consolidates PUCP's link with MIT, the No. 1 university in the world according to the QS World University Rankings 2023, and seeks to extend its reach in our country and region. In 2021. During a working visit, the MIT Emergency Ventilator Project 's research peers highlighted the fact that MASI is the only initiative in the world that has reached the hospital care stage. Thus, an important alliance for the development of medical technology in Latin America was born.

Now, the PUCP and MIT are organising this workshop with the aim of democratising health technology. Peru and other Latin American countries are importers of medical technology. Almost all of the equipment found in hospitals has been developed in the United States, Europe or Asia. "It is not possible that the power to create medical technology is within the reach of a quarter of the world's population. The eighth Millennium Development Goal is about participation, specifically 'Global Partnership for Development'. We have to make sure that the process is collaborative between different centres of health innovation," explains Nevan Hanumara, Ph.D., research scientist at MIT Mechanical Eng. and co-organiser of this event.

For Dr Benjamín Castañeda, director of PUCP Medical Devices and general coordinator of the MASI Project, it is essential to decentralise technological development. Why this urgency? He identifies two major problems. On the one hand, most equipment has not been developed taking into account our reality; and, we do not have any local technology support.

"We cannot expect to use a US-made tele-equipment in areas with poor connectivity and no electricity or specialised human resources. Such equipment was designed on the assumption that broadband is available. In addition, we have no local technical support. For example, during the pandemic, fans were missing and we had to repair the ones we had, but where are they repaired? Outside the country. As we are not producers of technology, we don't have a good after-sales service or response to problems like COVID-19," explains Professor Castañeda.

Six months before the pandemic, he recalls, there was also a shortage of incubators for newborns in different regions of the country. Peru did not have the capacity to respond to such demand. This is something that could be changed by partnering with other countries in the region.

This three-day workshop - organised by the PUCP Medical Devices line with the support of our Faculty of Science and Engineeringand the Vice-Rectorate for Research -will serve to identify talent in Latin America, partner and propose joint initiatives. "The intention of the workshop is to form a collaborative network between the most important actors with the necessary capabilities for technological development in medical devices. They come from Chile, Colombia, Cuba, Brazil, Mexico and Paraguay. They are people who have had the opportunity to develop technology and put it at the service of different societies in pandemics. And, in doing so, they have encountered many common difficulties in Latin America. Partnering together can help us overcome these often normative barriers," says Dr Castañeda, who is also a professor in our Engineering Department.

Shriya Srinivasan, Ph.D., postdoctoral associate at the MIT Koch Institute, stresses that events like this are key to decentralising knowledge, having an effective exchange of ideas and enabling access to technologies that are not available locally. "In addition, regulatory frameworks and payment methods can help offset localised challenges," he says.

For his part, Professor Hanumara of MIT stresses that this process must be collaborative. "While some healthcare needs are universal, there are others that are region-specific. In Latin America, there is phenomenal engineering talent that can develop solutions that meet the highest clinical standards. We want to make sure we don't lose momentum now that we are no longer panicking about COVID-19. We want to capture this partnership as a positive force in the future," he says.

To continue to grow, it is essential to remove barriers, including bureaucratic and regulatory ones. For example, Castañeda recalls that when developing the MASI ventilator, there was no established process for approval and use.

"It is a barrier of lack of experience at all levels of medical device development that occurs in Latin America. It starts with the same regulatory body that approves development initiatives. In Peru, medical devices are approved as if they were drugs. What does a company that wants to develop them need? It needs to hire a pharmaceutical chemist, which doesn't make sense," he says.

There are common problems, but we have been able to overcome them. The workshop will present experiences of successful technology development projects in Peru, Chile, Colombia and the USA, which were developed during the shortage of equipment to combat COVID-19.

How can we foster sustainable health technology innovation in Latin America that is appropriate, accessible and affordable while meeting the highest clinical standards? This overarching question will inform the debate and the development of initiatives. From it, they will identify opportunities for long-term collaboration to work together on global health challenges. In turn, they will foster discussions on strengthening local innovation ecosystems.

For Professor Hanumara of MIT, PUCP has a fundamental role as an educational and research institution. As a university, he sees it as a neutral territory that can change the mindset of professionals. At the same time, it has the capacity to bring together professionals and generate a group of convenience; and alliances in Latin America will be key to develop teams that fit our local reality. He also affirms that this partnership will allow MIT to continue learning and establishing connections.

"We have the case of the University of Antioquia. They set out to make ventilators. They started a project with a plastics company that never made medical equipment. They started making those parts and now they even sell spare parts for medical equipment and no longer need to import them. On the other hand, in Peru, there was a paradigm shift for the MASI Project to get state regulatory approval. In fact, that is the beginning of this whole discussion. It was the first medical device built and approved in Peru. Seeing this, we think we can do a lot together," summarises Ph.D. Nahumara.

Professionals from PUCP and around the world will give keynote lectures and present cases that show that there is potential in Latin America to close the gaps between medicine, engineering and industry. In addition, the programme includes a hackathon on topics identified by the participants and will culminate in a networking dinner.

It is expected to bring together up to 100 attendees including academic researchers, industry collaborators, clinical leaders, hospital and local medical device industry officials, and government health and regulatory authorities to share experiences.